|

||||||

|

| In 2151,

Enterprise NX-01, the first human starship to travel with speeds far beyond the warp 2

reached by Earth Star Fleet ships up to then, thus getting the chance to explore regions

of deep space where no man has gone before, departs from Earth for its interstellar

mission of exploration. With warp 5, what is revolutionary up to this moment, but will be

a considerably low speed in the centuries to come, Enterprise and its crew surveys what

will become the "Galactic neighbourhood" of one big United Federation of Planets

in the 23rd and 24th century. This chapter's goal is to explore the Cartography and (specifically) distance issues which are (deliberately, but - "thanks" to various scientific and continuity problems in the fifth Star Trek series "Enterprise" - more often unintentionally) tackled in the course of this mission. |

|

The speed of Enterprise NX-01

To deal with maps and distances regarding the starship Enterprise, we first have to nail down its maximum speed, which will be, judging from the already aired episodes, apparently far more often and regularly used than the maximum speeds of the Starfleet vessels to come, what is, from a production-wise point of view, no surprise given that every speed lower than this (already quite low) warp factor would make the travels shown and distances bridged even more unbelievable.

The "low tech" warp core of Enterprise NX-01 |

As we know from the background "Bible" excerpts of the show, Enterprise is supposed to travel with warp 5. The on screen dialogue in the pilot "Broken Bow" (between chief engineer Charles Tucker and the newly arrived senior officers, in engineering) suggests an up to then reachable speed of warp 4.5, and indeed it seems this episode, and the depicted mission, does not feature a higher speed. However, the first regular episodes ("Fight or Flight") will introduce the aforementioned maximum speed rather unspectularly, so that there remains no doubt regarding Enterprise's speed limit at least at this early point of the mission (Who knows what future upgrades the writers will imagine?) |

However, the actual question regarding

Enterprise's speed is - how fast is warp 4.5 and warp 5, respectively, in this series? Of

course, we can ask this question for every series and every movie - given that the writers

prefer to use "plot drive", i.e. make warp speeds as fast as needed in the

respective episodes, anyway. However, it remains a fact that certain warp scales and warp

formulas have been derived, stated in background documentations like "The Making of

Star Trek" and the ST:TNG TM. It is true that this stuff can be only regarded as

"semi-canon" at best, as non of the formulae have been ever directly mentioned

on screen, however, at least the formula from the latter documentation has been obviously

used in the post-TOS Trek series TNG, DS9 and VOY, given that we can reproduce many of the

figures given in dialoge (like "it will take us x hours at warp y to reach z").

As mentioned in chapter 1.2, the post-TOS warp formula that fits best the graph given in

the ST:TNG TM is

v/c(w)=w(10/3)+(10-w)(-11/3)

a funcion converging against v/c(10)=infinity (that's what we call a "vertical asymptote") as the theoretical maximum warp speed. TOS, however, did not seem to use any consistent warp scale. Nevertheless, the mentioned "Making of" book establishes the much simpler formula

v/c(w)=w3

for speeds in the Original Series, a formula that has been adapted by most of the fandom literature since the 1960s.

Given this situation, there are three possibilities regarding Enterprise's "actual" speed (in multiples of the light speed rather than a obscure warp factor)

it is calculated according to the TOS scale

it is calculated according to the TNG scale

it is calculated according to yet another scale

If we consider "Trek

explanations" for the different warp scales, we quickly realize that possibility 2

makes no sense. The TNG scale is, as noted, much more complex than the TOS scale, which

does not feature any asymptotes but only a simple exponential increase. It has therefore

been suggested that in the 100 years between the two scales, the understanding of warp

physics has been deepened, and thus the scale was refined according to the new insights.

Now obviously it would make no sense that a century before TOS the TNG scale was already

in use, while it was abandoned during the times of Captain Kirk only to be reintroduced in

the 24th century.

Given that possibility three isn't an option either, as this scale, no matter how it

looks like, would need to produce slower speeds than the TOS scale anyway, one has

to come to the conclusion that the formula from "Making of Star Trek" would

indeed fit best in the 22nd century.

Unfortunately, technical consultant Andre Bormanis suggested the use of the TNG scale in "Enterprise", as the producers and writers are - of course - very interested in making the ship as fast as possible, even if it means to disrupt the scientific credibility of the show, sadly. However, as we will see, at least the pilot does not concur with his statements, but surprisingly supports above mentioned conclusion.

Indeed, we have two points of evidence

supporting the TOS scale which are actually mentioned in the pilot and are therefore

canon. By the way, I ignore Zefram Cochrane's statement in this episode of the new warp

speeds being "a hundred times faster" here, as speeds of 800 to 1,000c (given

that background sources mention a top speed of warp 2 for the other Star Fleet ships, and

"Fortunate Son" confirms this with a top speed of warp 1.8 for the there

featured cargo ship) clearly contradict the lower (!) travel speeds of Kirk's Enterprise,

as they are almost in range of 24th century top travel speeds.

1) "Neptune and back in six minutes"

This is mentioned right in the first

minutes of "Broken Bow", in the shuttle pod inspection scene. From the dialogue

we know that this destination can be reached at said time (supposedly from Earth, as they

are near Earth at that time, and it would make no sense for a human to give such a figure

thinking in other than geocentric terms) at warp 4.5, the speed finally applied in the

two-parter. If we do the math - bridging the 4,497,000,000 km

between Earth and Neptune in 6min/2=3min=180s - we get a speed of app. 24,983,333 km/s,

what equals roughly 83c. TOS warp 4.5 equals, according to the formula, 91.125c, what is a

rough match given that the writers (or whoever came up with these figures) may have worked

with less accurate values, while TNG warp 4.5 = 150c is certainly not within the tolerance

range anymore.

2) "Thirty million kilometers per second"

Even more convincing than above - slightly vague - evidence is the scene in which Enterprise actually jumps to warp 4.5 for the first time, with the warp factor slowly increasing and Captain Archer - as one of the very few times in Trek - actually mentions a direct speed figure which can be associated with a warp factor. Evidently, some time after Enterprise has passed warp 4.4 (the last warp factor to be mentioned in this scene, though we know they're heading for 4.5), Archer mentions that they're travelling at 30,000,000 km/s, that is, without any calculations, about 100c. Using the above pointed out values, this is again a rough match with TOS warp 4.5 (100c would be warp 4.64), while TNG warp 4.5 are nowhere near this value (otherwise it would be an error of 50%!).

Now, while it is certainly clear now that the "Enterprise" writers and/or technical consultants were using the TOS scale for the figures in the pilot, statements like that of Andre Bormanis (made some time afterwards) and other - though not that clear and conclusive - proves in following episodes seem to hint a change of mind regarding the scale to be used in the show. As I stated, it makes no sense to apply a scale that apparently won't be introduced before two centuries in the future, and we also shouldn't forget that Enterprise has to remain, by all means, considerably slower than Kirk's Enterprise, let alone the high warp starships to come, in order to avoid problems with species, territories and phenomena which then "should be known" according to the speeds and thus distances Enterprise can travel, but clearly aren't known until the 23rd or 24th century given that those things have been mentioned as "first time occurrences" there. The "Enterprise" writers are walking a thin line here, pursuing "plot drive" episodes as in the past (already proven by the pilot, as we will see) yet having close restrictions when it comes to maintain the inter-series continuity in this especially demanding case of a prequel series, i.e. a series predating events of 600 episodes and 10 feature films.

The operation range of Enterprise NX-01

But let's take a closer look at how imminent this danger of "being too fast for credibility" is. If we take a look at the official map of the Galactic neighbourhood as it looks like in the 24th century (in the Star Trek universe, anyway), and discard the Klingons as first contact with them (to be dealt with in section 5.2.2), and a short trip to their home world, is the topic of the pilot, we have three major players - the Cardassians (and Bajorans), the Ferengi and the Romulans - that shouldn't be known by Enterprise by now. While we may neglect the case of the Romulans for the moment as we know that Earth will make First Contact with them a few years after 2151, clearly putting them in the ultimate operation range of Enterprise and the other warp 5 starships to come, we know for sure that Cardassians, Bajorans and especially Ferengi (given that we saw first contact with them in early TNG) are races not to be encountered in the 22nd century.

Interestingly we can reduce this three

issues to one given that DS9 suggested - on screen as well as in documentations like the

ST:DS9 TM - that all three territories are located in the same region of space, separated

by only a few (in the case of Cardassia-Bajor) or a few dozen (in the case of

Bajor-Ferenginar) light years. We then have to only consider the distance of Earth to this

region in the Alpha Quadrant. As we know, this has been a hot topic for years as there

have been no definite figures, but only vague assumptions, but we know for sure that it

can't be much more than a hundred light years (let alone the distance for half of the

territory of the Federation, assuming that Earth is close to the the center, that would

work out with 4000+ light years!) given that trips from DS9 to Earth, even if we assume

high warp travels in all cases, only took a few days up to two weeks at best.

Indeed, Rick Sternbach's ST:DS9 TM gives merely 50.3 light years as the distance of Bajor

to the "inner perimeter of the Federation" and the "core worlds of the

Federation", respectively, what is, of course, a loop hole leaving the ultimate

distance Bajor-Earth still vague. In a recent interview, Sternbach assumed that this

"inner sphere" would have a radius of only 20 light years, what results in about

70 light years distance.

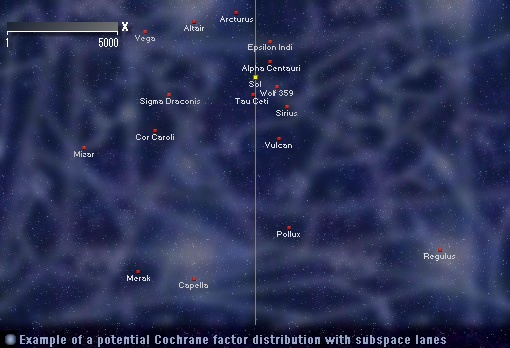

But is this really an issue? As the crew of Enterprise is "exploring", i.e. following every trace of unknown life or an inhabited planet it can spot, we may assume that they do not travel as "straight-lined", into one direction, as the ships in later series, whose tasks included directed survey, diplomatic missions and cargo / personal transport missions to a higher degree. At (TOS) warp 5, they theoretically could travel 72 light years per year, if we deduce at least 26 missions � 3 days (a purely arbitrary assumption) - not too much if we take into account the "zig zag route". However, already "Civilization" established that Enterprise travelled 78 light years in less than 3 1/2 months (the first on screen lines that seems to directly support the in this case rather inconvenient TNG scale - given that this equals about 271c = TNG warp 5.3 -, with a possible loophole - subspace "lanes" - to be introduced later). Even with my own assumption of altogether 120 light years as the distance Earth-Bajor (a compromise between the extraordinarily short travel times in DS9 and a "reasonable" distance) there is (literally) little space left for these three major players of the 24th century to remain undiscovered (of course, this is even more a problem for TOS and Kirk's Enterprise, though we cannot be sure if Cardassians and Bajorans weren't known at that time). At least for the Ferengi, which strictly must remain undiscovered until 2364, there is a partial explanation: a different distribution of power in the Alpha Quadrant in the 22nd and 23rd century could have made their relatively small territory unreachable for Earth / Federation ships up to a later date, for example, if the Cardassian Union completely surrounded their space at that time. This solution is hinted at in the Map of Local Space, though another one would be the "vastness of space" per se and the fact that the voyages of Kirk's Enterprise - and presumably those of Archer's Enterprise as well - focused on the Beta Quadrant and the there residing powers of the Klingon and (soon) Romulan Empire.

A final point we have to consider is

the popular question - if Enterprise only explores the supposedly well-known Galactic

neighbourhood of a few dozen light years around Earth (and, as we have seen, is also only

"allowed" to survey these region as everything farther away would lead to

serious continuity problems), why can they discover "strange new worlds and

civilizations" that are also new to us at all? Shouldn't they encounter only

species and planets well-known in the 23rd and 24th century, and therefore well-known to

us, while the Enterprise writers, which of course have to come up with something new and

unknown up to now, exactly aim at the opposite?

Now while it is not logical, if we think about it, the answer is - surprisingly - no. As

Star Trek's goal was always the exploration of the unknown and the farthest reaches of

deep space, and the technology was depicted as considerably more advanced in the 23rd and

24 centuries than it is in "Enterprise", our own "doorstep", the

"interstellar backyard" of Earth is still the most unknown region of all! Of

course we have Andorians and Vulcans and other species here, important players in TOS,

and, rightfully so, in "Enterprise" as well; yet what do we actually know about

the other planets and species here, in this (in the Trek Galaxy) supposedly densely

populated area of space? This "proximity paradox" actually makes the entire

series per se possible - to explore the unknown of Earth near space (what we will regard

as "Earth near" from the view of the 24th century, anyway) for the crew and the

viewer without overstraining continuity and credibility too much.

Still, the point of the maximum operation range of Enterprise, and the potential conflicts with (clearly) later discoveries and missions, remains unsolved up to now. While the producers may be aware enough of the issue to prevent more severe contradictions, in the end "suspending disbelief" may be the only way to buy the deep space exploration of Enterprise in the years to come.

5.2.2 The Qo'noS and "Rigel" issues

Unfortunately, it is (already) the

pilot that seemingly disrupts the hope for scientific credibility and continuity in terms

of Cartography in the new series. The entire mission of bringing back the Klingon pilot to

his homeworld, as depicted in "Broken Bow", becomes a bit unbelievable and

certainly does not concur with the "vastness of space" and the "deficiency

and primitiveness of technology" that is propagated by the producers and the episode

itself.

"Four days there, four days back"

| Several times in the pilot, it is

directly expressed how short the first deep space mission of Enterprise - allegedly a

mission that would have not been possible with prior starships, thus leading the crew into

uncharted territory - will ultimately be. If there wouldn't have been complications like

the "Rigel" detour (more on this separate problem in the next subsection),

Enterprise would have needed only 4 days to reach Qo'noS, the center of the Klingon

Empire, from Earth. Now generally, the gripe is basically the same as with the extreme closeness of Bajor and Cardassia as witnessed over the course of Deep Space Nine and ultimately given in the ST:DS9 TM (with slightly more than 5 ly) - how can Earth and Q'onoS be as close neighbours as suggested in "Broken Bow" given that these two planets will be the cores of two hundreds of light years large interstellar alliances, which will moreover have hostile relations almost resulting in open war in the 23rd century? |

|

However, this special case seems to be not only very unlikely in terms of interstellar politics (and as we see it wouldn't be the first time we have an inconsistency in this field), but also questionable in terms of science and technology. Using the speed figures given in the very same episode (and examined above), we can proof that - without further explanations - this whole scenario is not just unlikely, but actually impossible in this regard! 4 days at warp 4.5 - that works out to be 0.998 ly if using the TOS scale (and even with the TNG scale it's merely 1.6 light years), i.e. closer than the closest star to Earth, Proxima Centauri, which is 4.4 ly away. A very fine example for plot drive, isn't it? ;)

Obviously it won't be easy to explain away this major science blooper, yet there are some intriguing possibilities I would like to introduce here. Before we examine them, however, we have to consider the "Why?". Nothing, absolutely nothing in the story requires a journey of merely 4 days; the Klingon is physically stable, the crew must be very used to long journeys (given that none of them has travelled faster than warp 2 before), and we the viewers are used to Star Trek's narrative technique of cutting unnecessary screen time by showing an exterior shot and explaining passing time via log entries of the Captain. Now there are several log sequences over the course of the pilot which could have been used to make the same 90 minutes of real time to 4 weeks (instead of 4 days) narrative time. So what is it then? Ignorance? A major screw-up? I thought so for a long time, but perhaps not entirely. Because thinking about it, it's surprisingly not "Enterprise" that introduced this problem with Qo'noS distance, and I can very well imagine that the "Enterprise" writers relied on that earlier depiction, trying to make it more credible by being consistent to it. I'm talking about the events of "Star Trek VI", where the Earth and the whole Klingon Empire - Rura Pente, Kithomer and Q'onoS - seem to be extremely close given that the USS Enterprise, and later the USS Excelsior need days, if not less than a day, to travel from Earth to these locations. Even with the possibilities of the 23rd century, how can a Excelsior class vessel travel from the edge of the Alpha Quadrant (as mentioned by Captain Sulu) to Camp Khitomer on the same day? Obviously all these locations are all very close to Earth - if not regarding distance, then definitely regarding travel time (as we will see, these two measures are not necessarily proportional, as the standard warp calculation would suggest).

No matter how far Qo'noS is, it's

obviously farther away from Earth than Alpha Centauri... so we can actually only discard

the four days and pretend that Archer (and the others that mentioned such a short travel

time) said something different. However, there is one very elegant explanation for this

and similar cases, with that we can - amazingly - keep the hapless four days and still

put Qo'noS at some reasonable distance to Earth, without making Enterprise faster

than Voyager and Enterprise-E combined.

This solution is based on a premise first mentioned in the noncanon fandom literature of

the 1970s and 1980s, which is also hinted on in the semi-canon ST:TNG TM. There, you can

see the warp chart and the warp / multiples of light speed coherences mentioned earlier,

however, with the additional note: "the actual values depend on interstellar

conditions, i.e. gaseous density, electrical and magnetic fields and subspace

fluctuations". This little explanation gives us a lot of possibilities to solve a lot

of inconsistencies and problems that have occurred over the years, but in this case, where

the standard explanation is just impossible, it is urgent.

So how does it work? If warp factors are, in terms of their light speed equivalents, not

absolute, but only relative figures, depending on the local properties of space and

subspace, the multiples given are only minimum / average values. To express the

difference of these "idealized figures" and the actual values reached in

different regions of the Galaxy, the fandom literature (such as "Star Trek Maps"

by Geoffrey Mandel) extended the warp formula to

v/c(w)=c3 * X

with X being the Cochrane factor which expresses exactly the mentioned forces that boost warp and make a starship, travelling with the same warp factor (and thus investing the same amount of energy) one time much more faster than the other. If we take into account that the distribution of the properties associated with the Cochrane factor in space are not necessarily equal or random, we can hypothesize that there are certain "lanes" in space which differ from the rest by extremely high Cochrane factors. Whatever fictitious natural phenomenon is the reason for them (e.g. the "subspace currents" mentioned in [VOY] Displaced), in these narrow areas of Cochrane factor bursts a starship would travel some hundred times faster than outside, while, as an important aspect, the ship will - contrast to wormholes and similar phenomena which will even push forward a ship at low impulse with mentioned speeds - still need to travel at a considerably high warp speed to make the boosting effect truly effective. As you can imagine, this way much can be explained in terms of the "Star Trek VI" and "Broken Bow" issue, while it does not necessarily contradict the fact that there possibly already have been pre-Enterprise starships travelling at warp in the direction of Qo'noS without ever reaching it, given that they only travelled with warp 2 maximum (if you multiply warp 2 and warp 4.5 with a constant X, the proportionality factor will still remain the same).

Another point that supports the "Cochrane factor" explanation: you have to know where these regions of Cochrane factor bursts are in order to take advantage of them. In case of "Broken Bow" this shows the obscure "Vulcan star charts" (what for does humanity - having examined space for 4000 years - need star charts of the Galactic neighbourhood of a few dozen light years?) in a whole new light. What if these star charts do not only show the positions of stars, but also the network of temporarily or permanently stable regions of ultra-high warp speeds, revealing the Cochrane factors in the different regions in space, thus showing the fastest way to Qo'noS, which can be indeed travelled within 4 days, while you would need 40 days or longer to reach it if you would travel a straight line to the Klingon homeworld? It's not illogical at all - just think of route planning and how you will reach your destination faster using highways than using the direct way via smaller roads, while in the latter case the distance might be actually smaller than in the first case. In both cases, time and distance are two completely different aspects, as the possible maximum speeds considerably differ. On planet Earth, you use your street atlas to find out which streets you can use best to reach your goal in the shortest amount of time; in case of interstellar travel, you will probably need similar charts to plot your course.

Of course, with this explanation Qo'noS might be located anywhere, yet we generally have to make a few restrictions regarding the power of "Cochrane factor bursts". To my mind travels like the one of Kirk's Enterprise in Star Trek V to the center of the Galaxy (26,000 ly) in mere days are still errors. As pointed out above, you have to take into consideration: you'd probably have to chart the whole distance of a potential lane before you could use it, thus forbidding true exploration at incredible speeds (and, the other way round, a quick voyage home for Voyager in the 24th century). Only on pre-explored, well-known and often used routes (like the ones between Earth and Qo'noS, and, in the same vein, perhaps Earth and Bajor as well; a lane which wouldn't have been been charted before the 23rd or 24th century for obvious reasons), this advantage could be used. Otherwise, the possibilities would be just too far reaching, and make the lanes too important to keep them credible, given that they were never mentioned (fortunately their nature does not necessarily associate a visual phenomenon with them, as it would be the case with wormholes or subspace shortcuts) nor their effect shown (i.e. by constant travels of starships across the Galaxy). However, in all cases in which we just need boost by a factor of ten or one hundred for a anyway quite short distance, I do think this "plot device" is both useful and feasible. However, before we come to final guesses how far the Klingon homeworld might be away from Earth, another issue, that is raised in the course of the mission, has to be considered, as it is directly associated with this.

"Rigel" vs. Rigel

| At first glance, there namely seems to be one problem that apparently is a much grosser violation of real word science and inter series continuity: a star called Rigel plays an important role on the Qo'noS mission, as the Klingon pilot stopped there on his to Earth, and the Enterprise crew make a detour (if it is one at all) to this location as well, before they finally head for the Klingon homeworld. The problematic part: as it is pretty well known from school astronomy, Rigel is the Arabic name of a real star known for thousands of years; a real star that is 773 ly away (cf. "The positions of the real stars"). Now given what I mentioned above about Qo'noS distance and the time problem, this seemingly stretches the whole issue to ridiculousness. |

|

Even with the Cochrane factor explanation, it would

be a bit too much a rationalization to allow any starship, at any time, to bridge more

than 773 ly (+X ly, given that Qo'noS is not necessarily on route) within 4 days (I know

this happened in TOS, yet this was a major screw-up); and "Broken Bow" does not

support this at all anyway given that the star is merely 15 ly away from a

position Enterprise has reached from Earth within mere hours of flight. Additionally, it

seems that the writers were unaware of the true meaning of Rigel as a real star

anyway, as this is not only not mentioned, but contradicted in the dialogue. It seems

they just intended to add another TOS reference to their script. Fortunately, I might add,

because exactly this additional error makes the whole Rigel issue a non-issue, and -

unintentionally, I'm inclined to believe - solves the whole problem Rigel, as a much too

far away star whose properties (super giant with little heavy metal abundance and short

life span) would never allow life-capable planets, has posed in all Trek series it was

mentioned.

The important point is - in the respective scene, "Rigel" is mentioned together

with a few other star locations (among them Tholia) - as names directly extracted from a Klingon

database. How could the Klingons, which had no contact to Earth up to then, possibly have

the same Arabic name for the same star? Not at all, is the only answer. Obviously,

"Rigel" has to be a Klingon homophone denoting a different star than

our Rigel (I'm therefore using quotation marks for the Klingon Rigel, as it is surely

written different - even if the subtitles in a later scene show Rigel written in our way),

completely ruling out the assumption that the "Rigel" in the pilot is our real

star Rigel, and, as I pointed out, also explaining the frequent later reference to

"Rigel" in TOS, TNG and DS9 as a common, not too far planetary system, assuming

that the alien name, probably very common in the already existing interstellar community

(given that T'Pol very well knew what and where "Rigel" is), was kept by humans

as one of the few instances where Earth was influenced by outer influences and not vice

versa.

It all makes a lot more sense this way. Just to mention two major cases: the journey of

Pike and his crew back from "Rigel" to Vega (a star very close to Earth) in

order to treat the wounded in the very first TOS pilot "The Cage" - up to now we

had to believe that he travelled almost 800 light years within a few weeks and passed

Earth in order to reach another colony! And we have the "Rigellians", obviously

native to the "Rigel" system, as an important Federation species akin to the

Vulcans and Romulans (with respective planetary systems not too far away from Earth) - the

rationalization up to now had to be that the Rigellians colonized the Rigel system some

time ago, have a very resistant physiology, are an "outsider" species in the

Federation family etc.

Still, it is not necessary, nor reasonable, to make this revision in all cases Rigel was mentioned and / or played an important role. Indeed the Rigel problem is solved best by assuming that both "Rigels" were used in Trek. For example, in [TOS] Mudd's Women, Kirk did explicitly mention that the planet visited there (Rigel XII) is at the edge of the Federation, only rarely visited by starships, and after all, his ship, running short in Dilithium supplies, was threatened to fall out of orbit - not very credible if this Rigel was in the major system with lots of colonies, the home world of the Rigellians etc. that was mentioned in other cases. So we can safely assume that this "Rigel" was our Rigel. If we think about it, this way the scientific problems are solved as well - putting apparently close, busy M class worlds in the "Rigel" system and all others in the (our) Rigel system - explaining how there can be so many inhabitable planets (eight up to now, mentioned in more than a dozen episodes) in one planetary system.

Back to Qo'noS

Given that we have disclosed "Rigel" to be an unknown planetary system 15+x light years away from Earth, Qo'noS might be anywhere between this distance and about 50 light years as "acceptable" distance I would have chosen as a "safe minimum" before "Broken Bow" (cf. operation range chart). As we have found out, no matter what the actual distance is, only with daring (yet not conflicting with on screen canon) auxialiary constructs like the "subspace lanes" (then causing Cochrane factor increases between 1500 to 5000 percent) we will be able to explain the first voyage of Enterprise in a reasonably scientific way anyway.

Interestingly, such a short distance may not contradict the fact that the later series (TNG and DS9) seemingly put the Klingon homeworld, and the whole Klingon Empire, considerably farther away, so that e.g. reinforcements always needed a longer time (as seen in [DS9] The Way of the Warrior and [DS9] The Sacrifice of Angels). If we remember, Star Trek VI, which ironically was the first instance which demanded this extremely short travel time between Earth and Qo'noS, mentioned an evacuation and relocation of the Klingons living on this planet after the Praxis incident that allegedly made the homeworld uninhabitable within 50 years. Therefore, the Qo'noS we're talking about in Enterprise and the TOS feature films may be a completely different one than the planet we have seen in TNG and DS9. Even when acknowledging the fact that much can change within 200 years, on screen comparisons of the sky and planet color seem to support this idea, as seen in the following pictures.

|

|

|

|

� 1999-2002 by Star Trek Dimension / Webmaster. Last update: January 1st, 2002