|

Astronomy |

Overview

This chapter examines various real

astronomical problems occurring on Star Trek, as well as inconsistencies regarding the

geography of the Star Trek galaxy. It has to be clarified:

Why a quadrant

is not always a quarter of the Milky Way

Problem: In the original Star Trek series, the both measures "sector"

and "quadrant" are used contradictory. Both mean a spatial volume that is

considerably smaller than the Galaxy, but also fundamentally larger than a single

planetary system. Although "quadrant" literally refers to a "quarter"

and therefore should be logically used for naming a quarter of the Milky Way, it usually

refers to a smaller, sector-sized area of space, e.g. "quadrant 904" in [TOS]

The Squire of Gothos. Since Star Trek VI, that means the late 23rd century, commonly a

new, more correct quadrant system is used, according to which "the Galaxy is

subdivided into 4 quadrants, from which each forms a 90 degrees piece of cake, viewing the

Galaxy from the top or the bottom" (Star Trek Encyclopedia). However, the assumption

that solely this system is used seems to be wrong, since some Next Generation episode use

the term "quadrant" like TOS as a sector-sized region (e.g. the "Morgana

quadrant" in [TNG] The Child and Where Silence Has Lease).

Reasons: It is simple to explain why the

"quadrant" was originally used contradictory - at that time, the measures sector

as well as the quadrant weren't fixed at all und were used at will by the authors. They

were determined a long time after TOS, in case of the sector not before 1994, when the

Star Trek Encyclopedia was published. While there hasn't been an on screen definition of

the sector up to now, the quadrant was defined for the first time already in 1979 for the

unofficial "Star Trek Maps". To scale the poster-sized maps of this project, the

Galaxy was divided into nine quadrants: quadrant 0 at the galactic core and four quadrants

North and South*. This subdivision of

three-dimensional space called "octant system" in mathematics more logical in

that respect that the Milky Way isn't a flat two-dimensional disc, but has a thickness of

5000 ly on average, with Earth being located 50 ly above the thought central dividing

plane, the so-called "Galactic plane". However, the system, as the maps

themselves, was never acknowledged by official sources nor regarded as "canon".

Believing the background sources, on the other hand, the quadrant system used in the new

series and the feature films and the distinction between the densely populated Alpha

Quadrant and the mainly unexplored Beta Quadrant was originally introduced to justify

Kirks remark in Star Trek II (premiere date: 1984) that the Enterprise is the sole

starship in the quadrant - even though this doesn't make this quote more credible (since

with Vulcan, Antares and Rigel, three important main planets of the Federation are located

in the Beta Quadrant). In Star Trek VI, this system was extensively used for the first

time, and the position of the large powers in the single quadrants was determined

(Klingons and Romulans in Beta Quadrant, Federation in Alpha Quadrant). Already before the

premiere in 1991, the new quadrant system was introduced for Star Trek: The Next

Generation with the episode [TNG] Der Barzanhandel, that aired in 1989. Therefore it

is logical that some TNG episode of the first and second seasons use the

"quadrant" differently, even though they play a long time after Star Trek VI.

Potential explanation: In the early and middle 23rd century, the

term "quadrant" was used parallel to the "sector", i.e. it referred to

a smaller area of space with a certain diameter. In the 2280s, a quadrant system was

introduced that is valid up to now. This system divides the Galaxy into four equally

sized, cubic quadrants. While most of the old quadrants were newly numbered as sectors,

some quadrant designations were kept as proper names for historical reasons, even though

they actually contradict with the common quadrant system. Therefore, there are even in the

24th century quadrants that do not carry the designations Alpha, Beta, Gamma or Delta.

Additional note: Read more about quadrants and sectors in

chapter 2.2 of the Star Trek Cartography "The

subdivision of the Star Trek Galaxy".

Why the

arrangement of the quadrants led to some confusion

Problem: The designations of the quadrants and their sizes

are commonly accepted and uniform to a large extent at the latest since [TNG] The Price,

where the Alpha, Gamma and Delta Quadrant were introduced, and Star Trek VI, which

mentioned the Beta Quadrant for the first time. On the other hand, the actual subdivision

of the Galaxy into quadrants led to some problems. The first edition of the official Star

Trek Encyclopedia, published in 1994, clarified that the Galaxy is divided into four

quadrants from which each forms a 90 degrees piece of cake, viewing the Galaxy from the

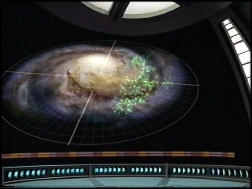

top or the bottom. Beside this description, a chart illustrated the arrangement of the

single quadrants, which was also re-used for the second and third edition of the Star Trek

Encyclopedia, as well as the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Technical Manual, how the following picture from the

Encyclopedia II shows:

According to this, the

quadrants are arranged fairly illogically, neither clockwise nor counter-clockwise: the

lower left quadrant is called "Alpha", the lower right one "Beta", the

upper left one "Gamma" and the upper right one "Delta". However, the

final arrangement of the quadrants was unimportant, since (labelled) charts of the Galaxy

were never used in Star Trek: The Next Generation or in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Apart

from the fact that according to the development in Star Trek VI Alpha Quadrant and Beta

Quadrant must be adjoining regions of space (what is natural in view of the designations),

the spatial situation did never play a role for the plot anyway. Therefore, the system was

accepted by the fans without difficulty and declared "canon" - until Star Trek:

Voyager aired. The new series dealt with the journey of the USS Voyager, which has been

stranded deep in the Delta Quadrant, back home to the Alpha Quadrant - what seems

logically if Earth is located exactly on the borderline between two quadrants.

Consequently, according to the official arrangement of the quadrants, Voyager would not

only have to cross the Delta Quadrant, but also the entire Beta Quadrant, before she

reaches Earth. Surprisingly, this fact was never mentioned on screen. Instead, the Beta

Quadrant was hushed up and virtually banished from the "Voyager" Galaxy.

Although it plays an elementary role with regards to the sphere of influence of the Borg

and the Romulan and Klingon empires, and therefore should be mentioned in the series,

there are not more than two reference in 145 episodes: in [VOY] Before and After ("like

the Yattho from the Beta Quadrant, who can predict the future [...]") and in

[VOY] Timeless ("Starfleet found a Borg cube wreckage in the Beta Quadrant"),

with the first quote being rather trivial. Moreover, there are increasingly references

regarding the Alpha Quadrant which should actually concern the Beta Quadant, like in [VOY]

Barge of the Dead ("The simplest explanation is that the Borg assimilated a Bird of

Prey somewhere in the Alpha Quadrant" - not likely the simplest explanation).

Although in the sixth season, Voyager is only a few thousand light years away from the

border of the Delta Quadrant, there wasn't any reference to the new quadrant in the entire

season. These clues corroborate the impression that Voyager does not need to cross the

Beta Quadrant at all to reach Earth, and consequently the Alpha and Beta quadrants must

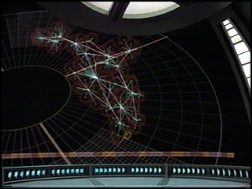

be swapped. This assumption is apparently confirmed by [VOY] Message in a Bottle,

because it was shown in this episode, what was only implied before: according to several

references in the dialogue, the USS Prometheus was located in the Alpha Quadrant, but the

map shown in the Astrometric Lab definitely marked its position in the lower right

quadrant. The farthest station of the alien relay network is situated there as well, that

spreads up to the "deep Alpha Quadrant" according to the episode.

|

|

Therefore, many fans

accept a counter-clockwise quadrant system with this "on screen evidence",

justifying this decision with the generally accepted rule that facts introduced in

official documentations are only "canon" as long as they don't contradict with

the episodes and feature films. And indeed, the official quadrant system introduced in

1994 was never shown on screen - neither in Star Trek: The Next Generation nor in Star

Trek: Deep Space Nine.

Reasons: As Rich Sternbach has indicated*,

the writers try to avoid to mention the

Beta Quadrant as far as possible simply because they think this would confuse casual

viewers, who only know that the crew of Voyager has stranded in the Delta Quadrant and now

wants to get back to the Alpha Quadrant, since that is the region where Earth is located.

The surely know that Voyager is very near to border, however, according to the series'

premise they like to remain Voyager in the Delta Quadrant until it finally finds a way

back to Earth, what certainly does not happen before the second half of the seventh

season. Consequently, detours and astronomical obstacles are cited as reasons why Voyager

still hasn't reached the Beta Quadrant. Of course, this lack of references concerning the

Beta Quadrant has finally created the situation that at least those fans who are familiar

with the Encyclopedia are fairly confused regarding the quadrant system.

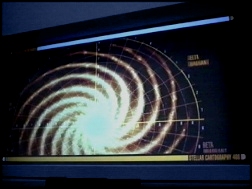

Explanation: In the end, the answer of the question what quadrant system is correct

after all is quite simple: in the 6th season, the official quadrant system from the

Star Trek Encyclopedia was shown on screen for the first time and therefore established as

fully canon. Probably, we owe the appearance of the (correctly) labeled Milky Way map in

the Starfleet Communications Center in San Francisco the people working at the Star Trek

Art Department, not the authors of the episode [VOY] The Pathfinder Project - perhaps even

as a reaction of the postings of many confused fans in various newsgroups and forums.

Anyway, this map is much more definite than the (non-labeled) charts and indirect

statements in [VOY] Message in the Bottle, so that we can forgot these embarrassing

errors.

|

|

However, what -

according to the statements of the crew - the empires of Klingons and Romulans, the home

planet of the Vulcans and the farthest outposts of the Borg have familiar with the Alpha

Quadrant, seems to be a different question ...

Additional note: Read more about the quadrants in chapter 2.2

of the Star Trek Cartography "The subdivision

of the Star Trek Galaxy".

What real star

Vulcan orbits

Problem:

During the 35 years covering history of Star Trek, the starships of Starfleet - the

Enterprise, the Voyager, the Defiant and many more - have visited hundreds of planets.

Thirty-seven of those planets orbit real stars of our Milky Way, e.g. Rigel IX, Antares IV

and Tau Ceti Prime, so that we can exactly determine their situation relative to Earth in

the meantime. Most positions, however, remained unknown, what isn't necessarily a bad

thing regarding worlds which only played a role once in one episode. But - a frequently

raised but rarely answered question of the fans is the query what star the probably most

famous fictitious Star Trek planet orbits; those extra-solar world with which Earth made

first contact on April 5th, 2063: Vulcan.

Reasons: Although the home planet of the Vulcans,

like its inhabitants, is one of the most important and popular elements of the Star Trek

universe and the setting of numerous episodes, the name of its system and therefore its

position remained a mystery during the original Star Trek series. Sadly, the feature films

and the later Star Trek series continued this tradition, and the Star Trek Encyclopedia as

well as all other official documentations ignored the issue.

Explanation: Due to the lack of an on screen quote or at

least an official statement concerning the real star that Vulcan orbits is canonically

unknown, and we can only make assumptions, analysing the properties of known

real stars.

At least, the episodes

and movies, especially the legendary episode [TOS] Amok Time, provide some clues, limiting

the number of potential stars:

The star is located

in the immediate neighborhood of the Sun.

The dominance of Starfleet Command in

[TOS] Amok Time (e.g. no time delay of the communication) already implies an Earth-near

position. But Star Trek: First Contact and the official Star Trek history make a farther

distance from our star unlikely as well - otherwise, Vulcans wouldn't have been the first

aliens that had contact with the human kind.

The star is located

near the real star Altair, consequently being only one or two dozen light years away from

Earth.

The distance of Vulcan from

Earth can be determined even more precisely with the help of [TOS] Amok Time. The

Enterprise travels, from an unknown starting point, to Altair IV, making a

(inconsiderable) detour to Vulcan. Because the mission is very time-critical and only

covers a few days, the distance between Altair and Vulcan must be relatively small.

The Vulcan sun is an

orange-yellow star.

When we saw Vulcan for the

first time in [TOS] Amok Time, it was a reddish, hot world. Although this basic

characteristic was always retained, the properties of the Vulcan sun can only be estimated

since the more differentiated presentation of the planetary surface in the Star Trek

movies. Based on the orange light that shone on Spock during his Kohlinar in Star Trek:

The Motion Picture and the shades of orange of the mountains around Mount Seleya in Star

Trek III and IV, we can assume that Vulcan's sun is orange as well. It would then belong

to a different spectral class than our yellow sun (type G2) - either a high G class or a

low K class, while the luminosity class would be essentially the same (V). However, this

is a quite uncertain clue, since firstly, such details were rarely paid attention to

regarding the presentation of planetary surfaces (especially in view of the different

appearances of Vulcan in the various movies and series) and secondly, an analysis of the

color of a star based on the mere lighting conditions on a planet can be very deceptive;

only remember the orange-reddish color of the Martian sky caused by iron-oxide dust.

Based on the first

two, cogent clues we can still track down numerous stars in the neighborhood of the Sun.

Yet, very early - even before the premiere of the first feature films at the beginning of

the 1980s - two candidates had been chosen, since the fandom and some Star Trek

enthusiastic astronomers had dealt with the issue. The (unofficial) books "Star Trek

2" (published in 1968, by James Blish), "Starfleet Technical Manual"

(published in 1974, by Franz Joseph) and "Star Trek Maps" (published in 1979, by

Jeff Maynard, Geoffrey Mandel and others) mention the real star 40 Eridani (aka � Eridani) as the Vulcan sun, while

the "Star Trek Spaceflight Chronology (published in 1980, by Stan and Fred Goldstein)

list Epsilon Eridani. However, it isn't the case that we have

two equally suitable, but completely uncanon candidates for Vulcan's sun. Indeed, on the

occasion of the 25th anniversary of Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry himself, together with

three scientists of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center of Astrophysics, has examined the stars

in question and named one as the most likely candidate. The results were published in a

short letter in the specialist journal Sky & Telescope in July 1991. The following text

is an excerpt from the main part of the article*:

We prefer the identification of 40 Eridani as Vulcan's sun

because of what we have learned about both stars at Mount Wilson. The HK Project takes its

name from the violet H and K lines of calcium, both sensitive tracers of stellar

magnetism. It turns out that the average level of magnetic activity inferred from the H

and K absorptions relates to a star's age; young stars tend to be more active than old

ones (Sky & Telescope: December 1990, page 589). The HK observations suggest that 40

Eridani is 4 billion years old, about the same age as the Sun. In contrast, Epsilon

Eridani is barely 1 billion years old.

Based on the history of life on Earth, life on any planet around

Epsilon Eridani would not have had time to evolve beyond the level of bacteria. On the

other hand, an intelligent civilization could have evolved over the aeons on a planet

circling 40 Eridani. So the latter is the more likely Vulcan sun.

In that case, Mr Spock's daytime star is a 4.4-magnitude multiple

system about 16 light-years from Earth. Presumably Vulcan orbits the primary star, an

orange main-sequence dwarf of spectral type K1. Data from the HK Project reveal that it

has a starspot cycle of roughly 11 years, just like the Sun. [Diagram here of 40 Eridani's

starspot cycle, showing that the latest peak in starspot activity was in 1989.]

Two companion stars--a 9th-magnitude white dwarf and an

11th-magnitude red dwarf--orbit each other about 400 astronomical units from the primary.

They would gleam brilliantly in the Vulcan sky with apparent magnitudes -8 and -6,

respectively.

SALLIE BALIUNAS

ROBERT DONAHUE

GEORGE NASSIOPOULOS

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

Cambridge, MA

GENE RODDENBERRY

Paramount Pictures Corp.

Los Angeles, CA

Consequently, 40 Eridani is our candidate. However, it has to be

considered to what extent this fact can be called "canon" or

"official", even if it has already been cited in countless fandom projects

(while it remains unknown who was the first to have this idea). But it is a fact that in

the same year, albeit some months before the publication of the article (on March 18th,

1991), the episode [TNG] Night Terrors aired, containing an in-joke regarding

40

Eridani-A, the main component of the trinary system 40 Eridani and therefore making at

least the star itself a part of the official Star Trek universe, even if there isn't a

reference to Vulcan: the dedication plaque of the USS Brattain identified the ship as

"Miranda class, constructed at 40 Eridani-A Starfleet yards". This plaque can be

seen in all editions of the Star Trek Encyclopedia, while again there isn't a note

regarding the significance of 40 Eridani below this and the "Vulcan" entry.

However, the article in Sky & Telescope is sufficiently crucial. In the end, a letter

that carries Gene Roddenberry's signature can't be less canon then the

"official" documentations of other highly ranked Star Trek employees like

Michael Okuda or Rick Sternbach. Just as we treat the Star Trek Encylopedia

and the

technical manuals, we should proceed here: as long as we hear or see nothing

contradictious in the series or feature films, 40 Eridani officially and canonically is Vulcan's sun.

Additional note: The positions and basic properties of 40 Eridani - as well as

the other real stars of Star Trek - are listed in the Star

Trek Cartography table "The

positions of the real stars".

Credits

Thanks to Geoffrey

Mandel, co-author of the Star Trek Maps, for the description of the quadrant system.

Thanks to Geoffrey

Mandel and Rick Sternbach himself for shedding some light on the Beta Quadrant issue.

Thanks to Brent Davies, who was the first to track down

the letter concerning Vulcan's sun and who has further examined the properties of this

star, and Winchell Chung, who has published the

complete article - together with many other exciting topics - on his website. More credits for the

makers of the interactive Star Trek: The Next Generation CD-ROM, which contains background

information on [TNG] Night Terrors, as well as Bernd

Schneider, who pointed the temporal correspondence of Gene Roddenberry's letter and

the episode.

|